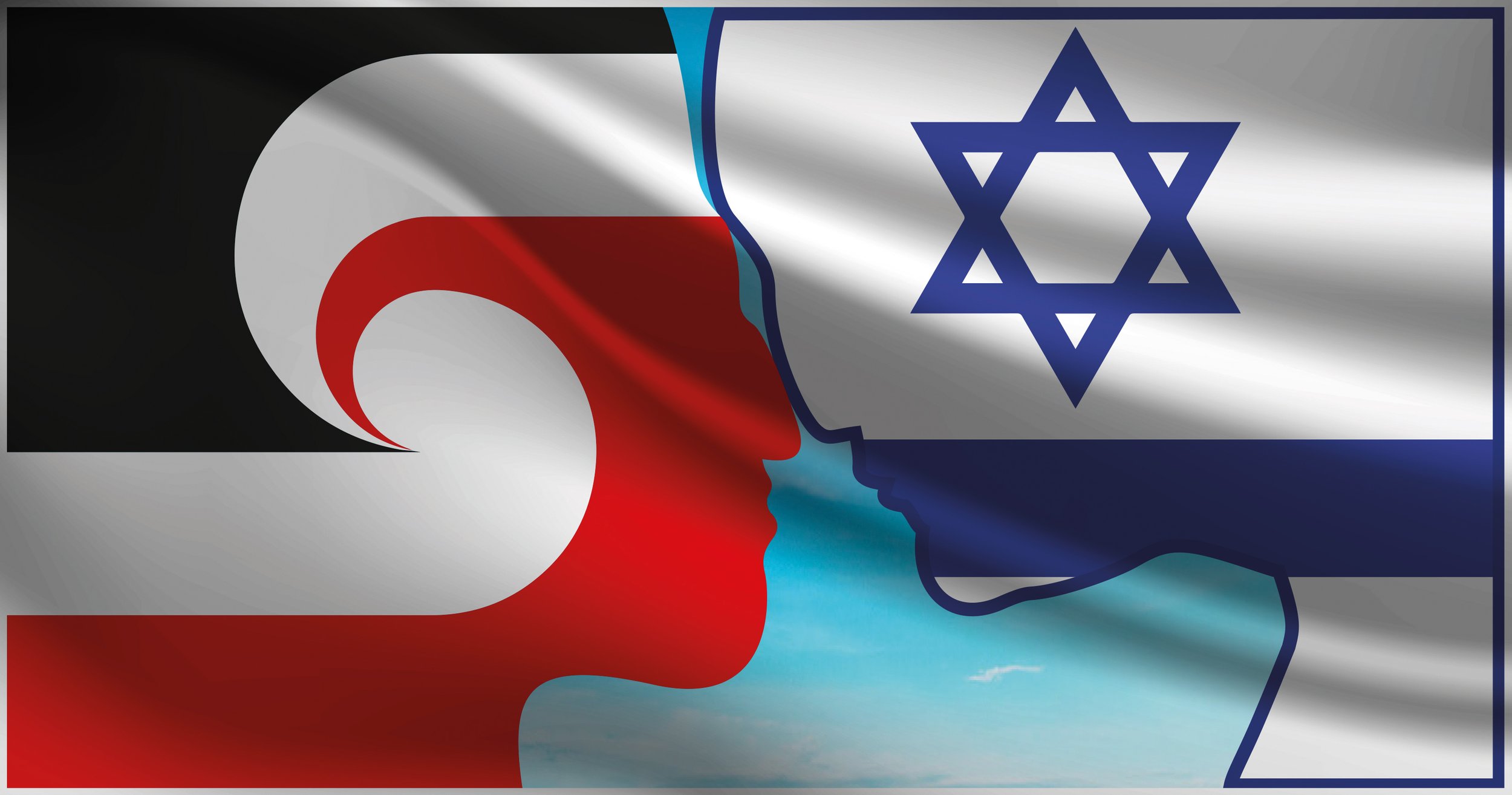

The Māori parallel to the Jewish experience

Image credit: Janet Curle

Ben Kepes is a Canterbury-based entrepreneur and professional board member.

OPINION: I'm fortunate to serve on the board of an iwi organisation. Having the opportunity to get to know more about Te Ao Māori, even at a slightly superficial level, is fascinating.

One concept that I've started to get to terms with is ahi kā, that literally translates to the burning of fires. Ahi kā speaks to the continuous occupation of whenua by iwi, runanga and hapu over a long period of time.

Ahi kā touches the physical and spiritual – the literal lighting of fires for cooking and comfort, and the metaphorical intergenerational sense of place that weaves into the consciousness, like smoke drifting over the damp grass on a still morning.

Ahi kā, to me, explains why Māori feel the pain of dislocation from their land so viscerally. To Māori, the whenua is more than somewhere to plant crops or lay one's head, it is the embodiment of generations of forbears, generations of shared context, and a sense of place.

It has been interesting in recent weeks to hear people opine on the Middle Eastern conflict claiming intersectionality between Māoridom's experience and that of the Palestinian people.

From Te Pāti Māori leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer to Green co-leader Marama Davidson, there have been many claims that Māori have an intrinsic connection to the Palestinian situation rooted in their own sense of dislocation.

The situation in the Middle East, however, couldn't be more different from that in New Zealand. Here in Aotearoa, a people travelled by waka to a group of islands that were uninhabited.

In those lands they settled, put down roots and became one with the land. A thousand or so years later, a colonial power descended upon the land, ripping the indigenous people from their homes and generally disrupting their sense of place.

The history of the area around modern-day Israel is completely different. The Middle East has been inhabited since prehistoric times by people on a gradual migratory journey out of Africa. The cultures that have called the region home, even temporarily, have been varied. One thing has been constant for several thousand years – a Jewish presence in the land.

I remember visiting an archaeological site in Israel and looking at the strata covering tens of thousands of years of occupation.

At the time I cogitated on the people who had lived, loved and mourned and whose memory was lost, like smoke into the sky, over the millennia. I was, frankly, a little depressed at the futility of it all.

Spending time coming to terms with concepts like ahi kā, however, showed that those collective memories were not lost. They are wrapped up in the songs, the stories, the food and, most fundamentally, the connection to the land.

Indeed, the area has its own version of ahi kā, a shared concept of connection to the land, of turangawaewae.

Over all of that time, there has been a continuous presence of Jews in the region; poignantly, millions of Jews who had been dispersed to the four corners of the earth by conquest or expulsion continue this connection with the land.

Israel is, quite simply, the cradle of our people – woven into our shared genetics, history and archeology. Our liturgy and literature, customs and conception of ourselves are rooted in the land of Israel.

It is true that for thousands of years, this presence was tiny and that the formation of the State of Israel and the post-Holocaust migration have changed the dynamic from one of being a largely impoverished minority to being the dominant population base.

Framing the Israel situation as colonialism lacks even a rudimentary understanding of the situation. Jewish migration to Israel is rooted in the Jewish psyche as “return”, not “colonisation”.

There are other people who feel this connection. Christians see Israel as the location of most of their holy sites. Israel has become a centre of importance to Muslims.

It is for this very reason that in 1947 the British offered up a plan to create a two-state solution in the region, with one state for the Jews and one for Arabs. This was accepted by the Jewish leaders. The Arab leaders responded by declaring war on the Jewish population and vowing to obliterate the fledgling state.

Framing the situation as one of 75 years of colonial Israeli aggression against a peaceful indigenous victim population is just obscene.

Referencing colonial occupation with the current focus on Gaza is bizarre. From 1967 to 2005, the Gaza Strip was a part of Israel, with many communities and settlements resident within it.

In 2005, Israel left Gaza – removing all residents, dismantling settlements etc. They gave total control of Gaza to the Palestinians. In terminology that Māori will be au fait with, Palestinians in Gaza were given rangatiratanga over the lands they inhabited.

The situation in the region is both tragic and highly complex. It is a region that has a history, since time immemorial, of war and division. It fires passions of an unholy (and, sometimes, holy) nature. But it is the place of ahi kā for the Jews and always will be.