Israel & Māori Connect on Geothermal Project

Tauhara North No.2 Trust chair Ngahi Bidois with HE Ambassador Ran Yaakoby

First published on Times of Israel

Israeli Ambassador to New Zealand, Ran Yaakoby, recently met with members of the Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa tribe, whose traditional territory lies between Lakes Taupo and Rotorua in New Zealand’s North Island .

Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa are not the largest tribe in the region, but what they lack in size they make up for in passion and vision, summed up in the tribal saying,

Ka ora te iwi, ka ora te tangata. ‘Wellbeing for the tribe, wellbeing for the people’.

While geothermal power provided the link between the Ambassador’s visit and the iwi, the meeting revealed other connections between the respective peoples.

In Māori society it is customary to share one’s whakapapa (genealogy) by way of introduction. The Ambassador traced his ancestry back to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and the descendants of Ngati Tahu-Whaoa to their ancestor Ariki Tahu Matua, who arrived in Aotearoa prior to the great migration of seven canoes from Hawaiiki.

Māori have experienced the negative effects of colonisation, as has Israel. While the tribal history of loss and trauma spanned the past century and a half, Ambassador Yaakoby’s narrative covered millennia. He spoke of the colonisation of his ancient homeland by various occupiers; Greeks, Romans, Byzantines. The Spanish Inquisition dispersed his ancestors around Europe and they ended up in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe. After the trauma of the Holocaust his forebears chose to leave Europe and to immigrate to Israel immediately following the Jewish state’s Declaration of Independence in 1948 - thus closing a circle that lasted many generations.

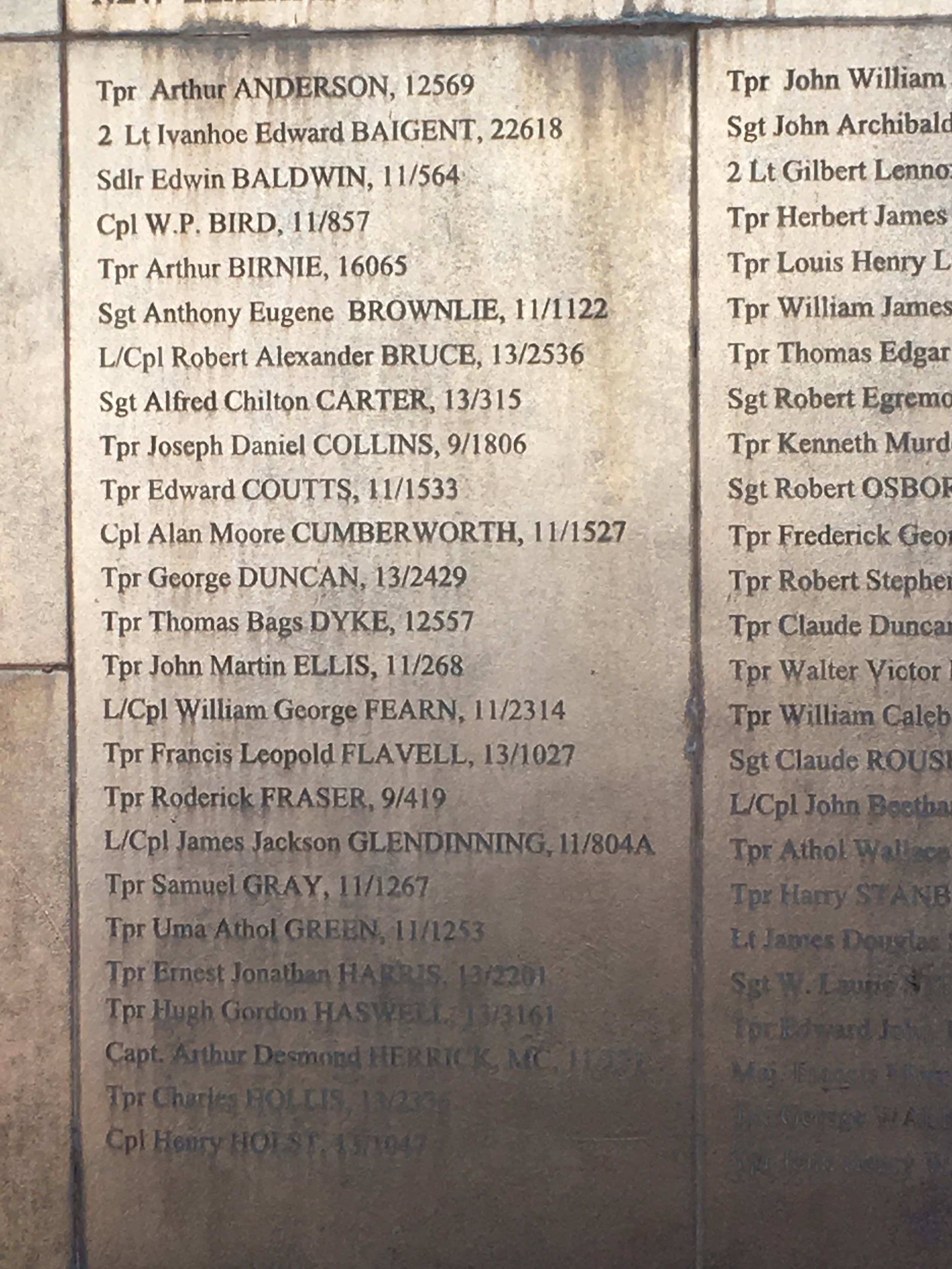

Ambassador Ran also acknowledged New Zealand’s brave soldiers, among them the Maori Battalion, who fought and shed blood in the cause of freedom during the two world wars. He explained that he had visited the graves of those buried in Israel. This was a moving point of connection for members of the Iwi whose ancestors had fought, died and been buried on the other side of the world.

While the timeframe for Māori history is shorter, many elements are similar.

Since the arrival of their ancestor Ariki Tahu Matua, Ngati Tahu-Whaoa had asserted and maintained governance (mana whakahaere) through continued occupation (ahi karoa) and possession of their lands and treasures (taonga). Prior to the arrival of European settlers to Aotearoa New Zealand, Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa was an autonomous, independent and self-governing confederation of sub-tribes.

After the establishment of the Native Land Court in 1865, Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa were “awarded” 370,000 acres of their traditional lands. However, under the Public Works Lands Act 1864, the government confiscated land for roads and services so that only 11,000 acres remained for the Iwi.

In the exercise of their chieftainship (rangatiratanga) the tribe have sought to hold fast to their land.

Kia Mau ki te whenua

Whakamahia te whenua

Hei Painga mo nga uri

Whakatipuranga

“Hold fast to our lands and make the best use of our lands for future generations.”

Traditionally, Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa were actively engaged in commerce and trade. Their people had seasonal cultivations spread throughout their traditional territories, capitalising on microclimates, diverse soils and winter and summer safe areas. Prior to the establishment of the Native Land Court in the 19th century, they were essentially autonomous and economically prosperous. Their people produced and sold commodities such as cattle, pigs, duck, vegetables, wheat, oats, potatoes, flax and timber. Ngati Tahu-Ngati Whaoa used produce such as red ochre, kereru, tuna, fish and minerals from their geothermal resources for customary trade with other iwi.

By the 21st century, many of the Iwi’s people had been negatively impacted by issues such as racism, unconscious bias, low expectations from teachers, lack of role models and access problems. These combine with often difficult home circumstances resulting from inter-generational life cycles impacted by the social and cultural trauma of colonisation and rapid urbanisation.

The Iwi therefore has a strong education and wellbeing focus with a strategy to support their people across the key areas of health, education, youth development, family, employment and housing. Innovation and leadership by example are key values promoted by the Iwi.

Today, the tribal area is primarily farmland and also has three hydroelectric stations, a dairy processing plant, a horticulture plant, forestry, four marae, and a number of learning institutes.

Like the Jews, many Māori have overcome adversity through a determination to hold fast to their values. Jews faced centuries of persecution and an attempted genocide in the twentieth century and yet regained sovereignty in their ancestral homeland and have built a thriving country for their people and for all those who would live in peace. Māori have suffered the loss of land and sovereignty (rangatiratanga) and faced the subsequent negative effects of intergenerational trauma and yet many have maintained their culture, regained some of their territories and are developing a vibrant economy. Both peoples are determined to work for the flourishing of their people and the land to find new and innovative ways to thrive and succeed.

Ambassador Ran gifted the Iwi an olive tree symbolizing peace; the gift of food, provided by the olives; warmth and light, provided by the olive oil; and the protection from the elements, afforded by the trunk and branches.

“As the tree, we need roots, as the tree we need the sun, the water and the soil, as a tree – we take care of this planet and of whoever needs our protection and shelter”. (Ambassador Ran Yaakoby)